The Fractal Trap: A Visual Model for Premature Complexity in Software Architecture

“Duplication is far cheaper than the wrong abstraction.”

— Sandi Metz, Practical Object-Oriented Design in Ruby

In the world of software design, there is a constant tension between planning for the future and addressing the present. Most developers have experienced the creeping urge to abstract, modularize, and generalize early—before actual needs have emerged. This often comes from a well-meaning desire to future-proof a system, to make it extensible and professional.

But premature architecture rarely does what we hope it will. It often adds complexity before the design has had time to stabilize, before the system has revealed its true shape. The result is a fragile lattice of assumptions—hard to modify, harder to understand.

This post offers a metaphor that helped me understand and communicate this challenge: a fractal. And although I first used it as a junior developer—and was largely dismissed for doing so—I’ve come to believe it’s a valuable mental model for anyone working with evolving systems.

Fractals as a Metaphor for Architectural Expansion

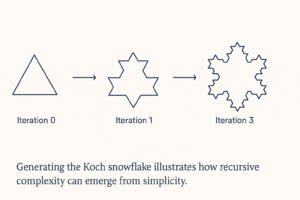

Fractals are recursive geometric patterns that generate complexity by repeating a simple rule at increasing levels of detail. A classic example is the Koch snowflake, which begins with an equilateral triangle. With each iteration, a smaller triangle is added to the center of every existing edge.

-

- Iteration 0: Simple triangle.

-

- Iteration 1: Triangle with bumps.

-

- Iteration 2+: Increasingly complex, spiky shape.

At first glance, this seems like a beautiful and scalable process—complexity emerging from simplicity. But here’s the key insight: as the complexity grows, the foundational triangle becomes increasingly difficult to change.

If you later decide that the base triangle should be a square—or even slightly stretched—every recursive addition depends on the original angles and lengths. Changing it breaks the whole system. You’ve painted yourself into a geometric corner.

Figure 1: The Koch snowflake begins with a triangle and recursively adds complexity—mirroring how over-architecture can evolve from simple systems.

Applying the Fractal Analogy to Code

In software, a similar phenomenon occurs when we apply layers of abstraction and modularity before they’re needed. For example:

-

- Creating interfaces for every class, even when there’s only one implementation.

-

- Building dependency injection frameworks for systems without actual dependencies yet.

-

- Designing for plugin support or extensibility without any clear use case.

These are architectural equivalents of adding detail to the triangle’s edges long before we know whether the triangle itself is shaped correctly.

And just like in a fractal, each abstraction layer or interface becomes a “recursive bump”—increasing surface area, but also increasing fragility. By the time you realize that the core concept was slightly off, you’re surrounded by an ornate, interconnected structure that depends on the original being right.

The Allure (and Danger) of Early Generalization

Premature abstraction often feels productive. It looks sophisticated. It demonstrates technical vocabulary and forethought. But as Kent Beck famously said:

“Make it work, make it right, make it fast.”

— Kent Beck, Extreme Programming Explained

In other words, get the triangle right first.

Martin Fowler echoes this in Refactoring:

“If you only need one implementation, don’t create an interface.”

Interfaces are powerful tools. They enable polymorphism, inversion of control, and testability. But when applied prematurely, they also create unnecessary indirection, slow comprehension, and foster rigidity. They are not inherently good or bad—they are context-dependent.

The same applies to architectural patterns. A pattern is a proven solution to a recurring problem. But if the problem hasn’t recurred—or hasn’t even appeared—then the pattern is not yet justified.

Simplicity as Strategic Patience

In systems thinking, simplicity is not a lack of intelligence—it’s a form of restraint. Choosing to build only what is needed is a discipline that comes with experience, not inexperience.

This is why many experienced engineers practice evolutionary design: allowing the system to grow organically, refactoring as real-world demands emerge. You refactor when patterns repeat. You introduce interfaces when variability appears. You abstract when extension becomes inevitable.

This is not laziness or short-sightedness. It’s intentional deferral of complexity, in the name of long-term flexibility.

Rich Hickey, the creator of Clojure, gave a talk titled Simple Made Easy where he distinguishes between simplicity (lack of interleaving, independence) and ease (how close something is to your current knowledge). Simplicity is a design goal. And it often means resisting the urge to add layers “just in case.”

Complexity is Not Free

In architectural terms, every layer—every triangle added to the edge—has a cost:

-

- Cognitive cost: more things to understand, even if unused.

-

- Maintenance cost: abstractions must be preserved, even when they’re not helping.

-

- Inflexibility cost: deeply nested abstractions are harder to refactor.

-

- Testing cost: interfaces demand mocks, which may not add value at early stages.

The assumption is that this upfront cost will pay off later. Sometimes it does. But very often, the future arrives differently than expected, and the extra scaffolding becomes dead weight.

What This Means in Practice

This metaphor isn’t a hard rule—it’s a mental model. Not all systems behave fractally. Sometimes early abstraction is necessary: in large distributed systems, shared libraries, or platforms with multiple consuming teams.

But for the vast majority of early-stage codebases or features:

-

- Favor concrete over abstract.

-

- Build only what is needed today, and design in a way that welcomes change.

-

- Let complexity emerge from real use cases, not imagined ones.

If you find yourself designing five layers deep for a need that might never appear, consider starting with a single triangle.

A Closing Thought

When I first shared this idea as a junior developer, it was dismissed as oversimplified, even patronizing. “Just use an interface” was the advice I got in return.

But over time, I’ve learned that many of the best developers do not build more than is necessary. They listen to the codebase. They treat abstraction as a tool, not a reflex. They respect simplicity—not because it’s easy, but because it’s fragile, valuable, and hard-won.

So the next time you feel the urge to design for everything up front, ask yourself:

“Am I reshaping the triangle, or am I adding triangles to its edges?”

And perhaps… wait until the system tells you it’s time.

Further Reading

-

- Kent Beck – Extreme Programming Explained

-

- Sandi Metz – Practical Object-Oriented Design in Ruby

-

- Martin Fowler – Refactoring

-

- Rich Hickey – Simple Made Easy (Talk, 2011)